Teams need to get their batting line-up straight

It's about time teams do away with a rigid batting line-up

Cricket teams generally comprise 7 batters with all, if not distinguishable, then at least complementary batting abilities, with an expectation that they can cruise their team to an above expected total for a major chunk of the innings. The basic expectation is, given a batter’s abilities and, more importantly, their inabilities, to maximize the return you can get out of a set of them. Teams do that by structuring a batting line-up in a way that each batter gets to, hopefully, play conditions that suit them best, where they can maximize their output in the form of runs. All of this can turn into a crock of shit if it’s thought about in an archaic, rigid manner, respecting the structure of a batting order like a linked list and not catering to the conditions on hand and their dynamism.

If Virat Kohli bats for your T20 side at No. 3, and if that’s a rational decision to begin with (since for most T20 teams today it isn’t), he cannot possibly be your ideal No. 3 bat in all conditions. Now when I mean ‘‘in all conditions,’’ I am not referring to how the pitch is playing out, but instead where the game stands right now, and what’s required of the batters that have not come out to bat just yet. If there’s an early wicket, you’d want Kohli to come and maybe do some damage control, play the anchor if that’s not a pixie dust in big 2025, see you through safe so that your team at least bats the full quota of overs. But if you have Kohli slotted at 3 and your first wicket falls in the 10th over, typically the point after which a lot of overs are bowled by spin (a match-up he prefers less than pace), it’s not all too rational to send him out then. You’re not maximizing on your batting resources.

In 2017, correct me if I’m wrong, Gautam Gambhir had Sunil Narine bat at the top to maximize on his potential batting output, which was a big step towards maximizing the complete batting arsenal a team has at hand. He brought forth the concept of a pinch-hitter in the zeitgeist, letting teams know that if they have a very aggressive batter slotted to bat at the back-end where they’re more likely to not bat than they are and where they batting resource goes to waste game after game, why not have them bat up top and go berserk from ball one. Best case scenario, your powerplay is set with your core batting line-up still intact, worst-case scenario, that pinch hitter wasn’t going to get that many balls to bat against in any case.

Batters favour different batting positions. That’s something we can all widely agree on, but I think we should look past what batting positions are on a team sheet and evaluate them based on when a batter comes out to bat. We should look at how different batters perform given different number of balls left to bat in the innings. Some may thrive at the top since they find semblance in forming their game with a considerable chunk of balls left to be bowled, some turn enraged with very little left in hand and can tap into their best game, while some may find their sweetest spot somewhere in the middle.

Let’s take a quick look at a batter to see if there’s any validity to what I’m saying. Let’s examine Hardik Pandya’s numbers since 2021 across different entry points—ignoring his designated spot in the batting order, as he has almost exclusively batted at 4 or 5—to determine if there are specific phases of the innings he has preferred more than others.

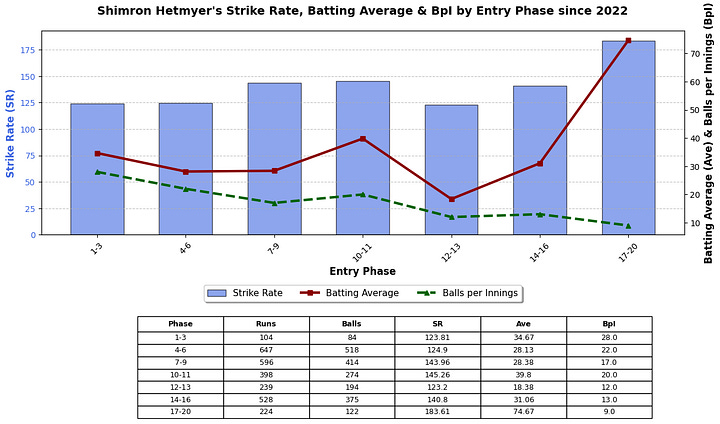

The x-axis indicates the batter’s entry point binned across different phases of an innings, so their entry point between overs 1-3, 4-6, 12-13, etc. On the y-axes we have the batter’s performance metrics such as SR, Average and the no. of balls faced in an innings. The Strike Rate bars are weighted by the runs scored by the batter in different entry phases

Since 2021, Hardik has come out to bat between overs 12-13 sixteen times, striking at 156 and averaging 41. Move that entry phase to 10-11 and he strikes at 117 with an average of 22. Phase 14-16, which is where he’s scored the highest number of runs hasn’t also quite been ideal for him, striking at 137 with an average of 25.

Dinesh Karthik was another guy who, very strongly, preferred an entry point either between overs 12-13 or 17-20.

Alright, but what now?

Well now we look at the data. We look at what different teams’ batting line-up comprise we look at what the numbers say, and we make an educated evaluation of when and how they should go about structuring their batters to maximize their returns.

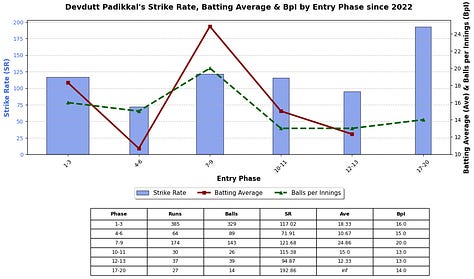

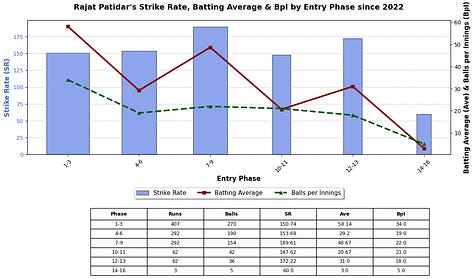

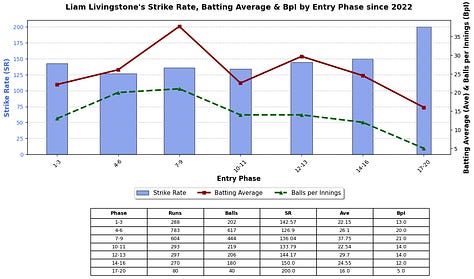

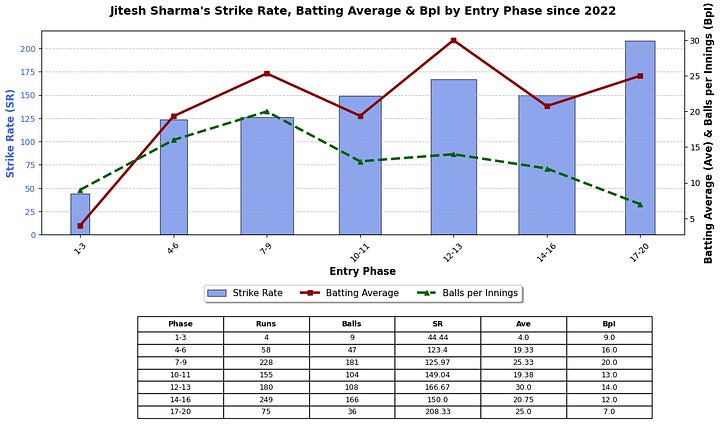

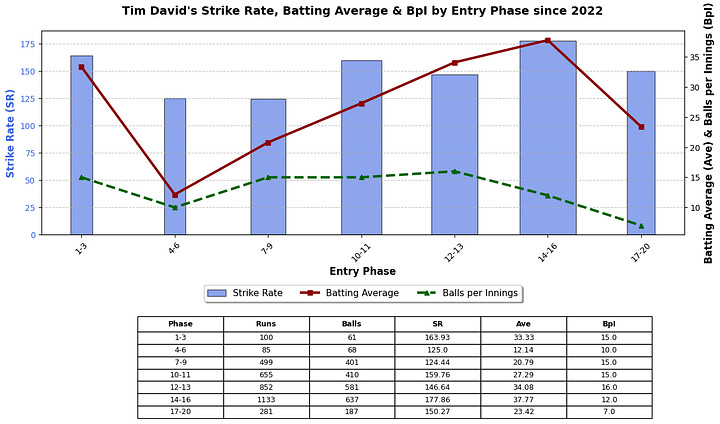

Let’s look at RCB in 2025 first. Below is a gallery comprising entry phase numbers for RCB batters Devdutt Padikkal, Rajat Patidar, Jitesh Sharma, Liam Livingstone, and Tim David.

RCB’s 2025 batting order by entry phases

Padikkal’s jotted up there with the rest simply because RCB has decided to stick with him in at No. 3, and he showed some really promising signs against CSK last night, taking Jadeja apart in that one over, being extremely dispensable with his wicket. In my opinion he doesn’t deserve a slot in this XII, but since he is RCB has to move around with him up there, and in any case this piece is about debunking what traditional batting positions can mean.

So first you have Rajat who, while he does great with an early wicket as well (striking 150 between overs 1-3 and 153 between 4-6, he’s an absolute monster when he comes into bat with 11-13 overs left on the board. In the 7 innings he’s done that, he strikes at an abysmal 190 while averaging north of 50. He bats almost 22 balls per innings when he comes out to bat between overs 7-9, so on an average he’s capable to giving a 42(22) innings when sent in that particular entry phase, and you’d get him out say 5 out of every 6 times. Pretty, pretty decent returns.

While RCB has had Liam come out to bat after Rajat, I think they would be better off swapping him with Jitesh given his prowess against spin and the former’s evident disadvantages against it. Jitesh has come out to bat between overs 12-13 8 times, batting 14 balls in each innings on average and striking at 166.7. That’s a 14-ball 23 teams get every time he’s come out to bat in that phase. What’s observable is that he’s made a majority of his runs in games where he’s come out to bat between overs 14-16. In that phase he’s, on average, scored 18(12) across 14 games. As the innings progresses and the value addition/dilution becomes steeper with each entry phase, it is crucial for teams to be spot on with when they send each batter in. The 3/4 balls that a no. 5 may take to get his eye in can cost the team more if done in the 15th over instead of the 13th.

Coincidental that both Livingstone and Jitesh have identical returns when they’ve come out to bat between overs 14-16, striking at 150 with an average of 12 balls played each innings (translating to an 18(12), just that Liam’s done it in 15 innings). That Jitesh has better returns between an entry phase of 12-13 than him, quite frankly he outshines him, makes a case why he should be the preferred option in that phase.

The final clink of that batting line-up is the monster that Tim David is. His preferred phase is overs 14-16, and he does really rather well there. He plays 12 balls on average every time he comes out to bat in that phase and strikes at 178, getting out almost once every 3 times. He’s capable of delivering a 22(12) on average while coming out to bat then.

These numbers, on their own, don’t mean much. It’s pointless to analyze them without considering the broader context of a particular innings. While Rajat may have a case for coming in before the first 10 overs are completed, it would be foolish to assume that’s the only ideal scenario—after all, the openers (and, unfortunately, Padikkal) aren’t going to get themselves out just to accommodate a batter who thrives in that phase. The purpose of this analysis was simply to see if the numbers align logically, and I believe this is exactly the kind of data that should be readily available to team management for making quick, informed decisions.

After 7 overs, the openers should be looking to score at a rate higher than what the next batter has historically managed in that phase. Kohli and Salt, for instance, should be aggressive enough to compensate for Patidar not being at the crease, leading to one of two possible outcomes—either they succeed and maintain a strong scoring rate without losing a wicket, or they get out, allowing a batter suited to that phase to step in. It’s time teams stop viewing T20 cricket as a collection of isolated individual performances and start recognizing that maximizing runs comes from leveraging complementary strengths and matchups in a cohesive manner.

Similarly, Kohli and Salt are able to stitch a partnership through the 15 overs, I wouldn’t mind them tossing the so-called batting order out the window and have Tim David come out to bat and do what he’s done so well and so often in the past. When looking at arranging batters in the middle and lower-middle order, teams should also be watchful of the ‘Balls per Innings’ count, for it means different things in different contexts and different entry phases of an innings. You wouldn’t want a batter coming out to bat between overs 12-13 and playing 25 balls on average play in his usual tempo if you have a batter whose strength is between 14-16 or 17-20 at a much higher strike rate. Reallocate the limited quota of overs available. Maximize all your resources given the 120-ball constraint.

KKR’s lower-middle order (that top to middle order isn’t something I’m ever keen on discussing) is also interesting to look at. Here are the numbers for Rinku Singh from 2022 and Andre Russell since 2022.

They both have resembling stats for their most favoured phase, which is 14-16, but what makes this duo works is them being cushioned with the ability of doing well up and down a bit too, with Rinku being a far better finisher if asked to come out to bat, where he can give a 15(7) on average, while Dre’s only managed like a 9(7).

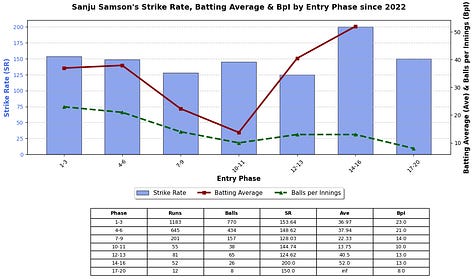

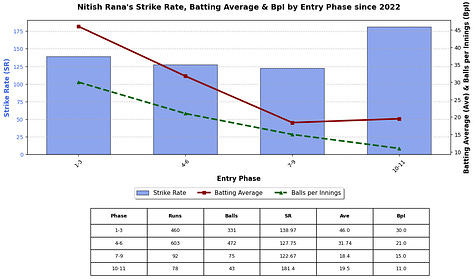

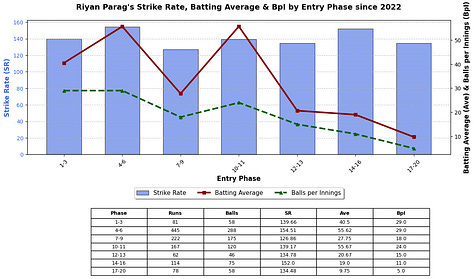

I’ll hold back on the commentary but here are the numbers for the top and middle-order bats for Rajasthan Royals in 2025 across entry phases. The exceeding overlap and bogging down too many batters with similar abilities (and worse, inabilities) shows why they’ve been of 2 minds the first 2 games they’ve played this year, and why they need a structural overhaul to make the resources at hand work.

RR’s 2025 batting order by entry phases

This is by no means a definitive metric for determining how teams should structure their batting lineup in every game. In fact, I don’t believe any set of quantitative metrics can comprehensively dictate the ideal batting order for a T20 innings. More emphasis should be placed on batter vs. bowler matchups across different phases and the different game conditions. However, misjudging a batter’s entry point can contribute to a team’s struggles during a match. The goal of this piece is simply to spark discussion and bring attention to nuances like these, as I believe a batter’s relative strengths and weaknesses at different entry points should be factored into planning an innings.